14K Gold Filled Jewellery: Packaging Design and Protection Strategies

2024-12-12

The bespoke jewelry packaging industry navigates a delicate balance between aesthetic luxury, structural engineering, and chemical preservation. Jewelry boxes bear the crucial responsibility of protecting valuable metals and gemstones from environmental erosion and physical damage. However, a systematic analysis of current market products reveals an industry rife with recurring design flaws. These flaws include catastrophic structural failures caused by substandard cardboard materials and hidden chemical corrosion of precious metals by reactive adhesives and acidic wood. In this article, Richpack provides a detailed technical analysis of these flaws, integrating materials science, woodworking engineering, and conservation chemistry to offer expert solutions for correcting these design defects.

The foundation of any jewelry box is its chassis. Whether constructed from paperboard laminates or solid timber, the chassis must withstand static loads during stacking and dynamic shock loads during transit. The prevalence of structural failure in this sector is rarely a result of poor assembly, but rather of fundamental errors in material specification. By understanding common issues with jewelry boxes and how to resolve them, manufacturers can prevent these baseline failures.

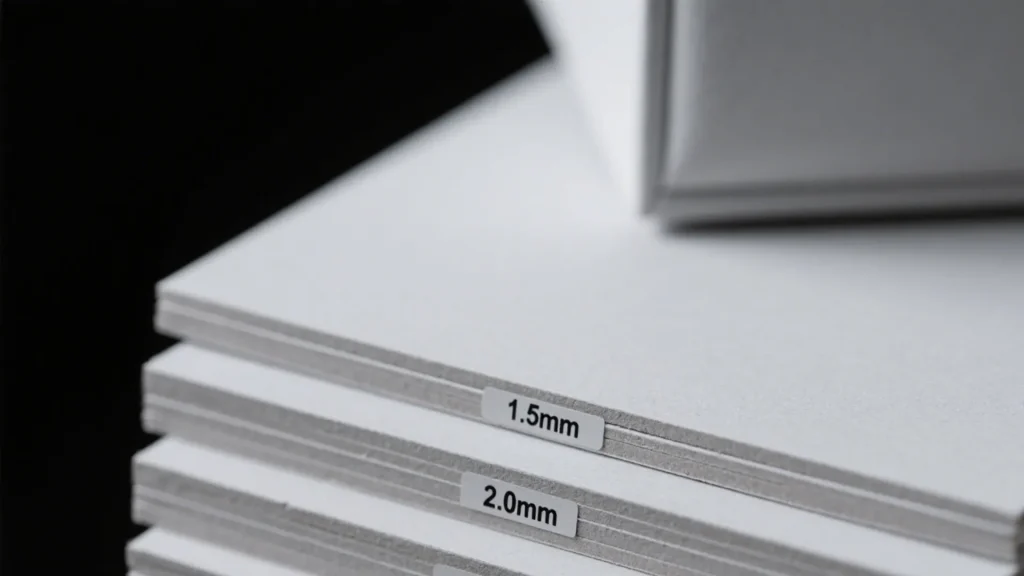

In the realm of rigid box manufacturing, the primary structural component is grayboard (chipboard). A pervasive economic fallacy drives many manufacturers and startups to specify 1.2 mm grayboard to reduce unit costs by fractions of a cent. While this thickness is adequate for lightweight confectionery, it is catastrophic for jewelry packaging.

The failure mechanism is two-fold. First, the lid experiences “diaphragm deflection.” When a 1.2 mm lid spans a distance greater than 10 cm, it lacks the flexural rigidity to resist the downward pressure of stacking or even the tension of the wrapping paper. This results in a concave warp that implies poor quality to the consumer. Second, the structural walls lack the compressive strength to support heavy inserts or magnetic closure mechanisms. When a heavy magnetic flap is attached to a 1.2 mm board, the repeated torque of opening and closing fatigues the hinge point, leading to delamination and tearing. This specific issue is a frequent topic in Consultations for custom jewelry packaging from Richpack, where clients often report dissatisfaction with the durability of standard generic boxes.

Optimal Specification Protocols:

To rectify these structural deficiencies, engineering standards must be aligned with the payload mass and box dimensions. The industry data suggests a tiered specification approach is necessary to ensure longevity:

| Board Thickness | Structural Behavior | Recommended Payload | Risk Assessment |

| 1.2–1.5 mm | Low flexural rigidity; prone to warping under tension. | Light consumables (soap, wax). | High Risk: Unsuitable for rigid jewelry boxes; conveys “budget” feel. |

| 2.0–2.5 mm | Moderate rigidity; withstands standard lamination tension. | Standard jewelry, cosmetics jars. | Optimal: Balances cost with tactile luxury and durability. |

| 3.0 mm+ | High rigidity; structurally inert feeling (wood-like). | Heavy sets, wine, electronics. | Premium: Maximizes protection but significantly impacts shipping weight. |

For existing inventory plagued by thin walls, a retrofit solution involves the internal application of a secondary liner board. By gluing a 1.0 mm cardstock sheet to the interior of the lid and base, one creates a “laminated beam” effect that significantly increases stiffness without altering the external dimensions.

While paperboard suffers from insufficient density, solid wood boxes suffer from the relentless physics of hygroscopy. Wood is an anisotropic material that expands and contracts with changes in relative humidity. A frequent design flaw in custom wooden boxes is the failure to account for this movement, leading to lids that cup (warp across the grain) or twist.

The mechanism of cupping typically arises when a lid is resawn from a thicker plank. If the moisture content is not perfectly equilibrated, or if one side of the lid is finished while the other is left raw, moisture exchange becomes asymmetrical. The side that absorbs moisture expands, while the dry side remains static, forcing the wood into a curve.

Remediation Techniques for Warped Lids:

Correcting a warped jewelry box lid requires re-engineering the internal stresses of the wood.

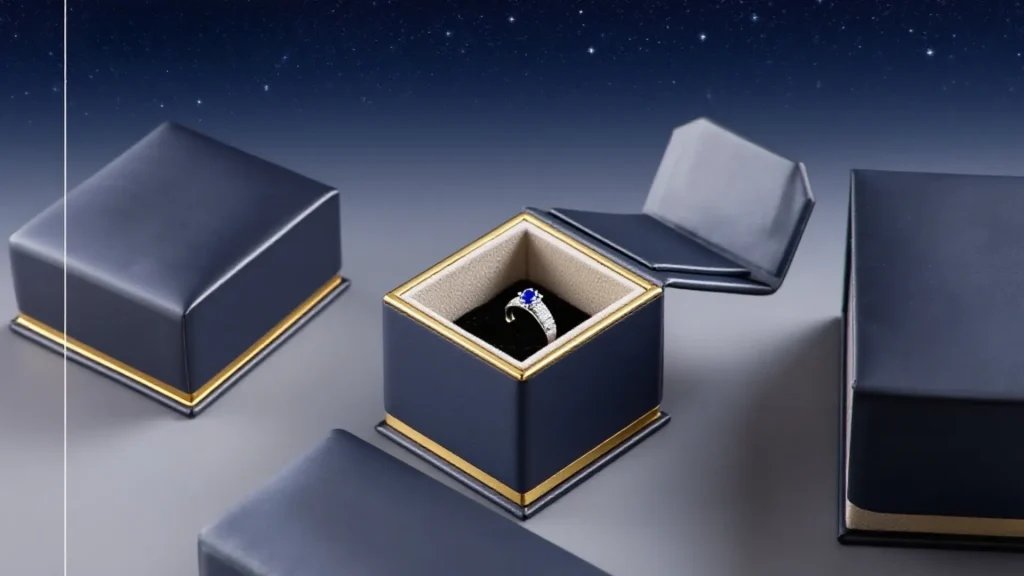

A jewelry box likes custom ring box, is often designed for the retail shelf but fails in the supply chain. The “single-wall fallacy” is a pervasive oversight where premium rigid boxes are shipped in single-wall (3-ply) corrugated cartons. This offers insufficient crush resistance against the stacking pressures of modern logistics networks.

Data from manufacturing audits and Inquiries about Richpack’s custom jewelry packaging reveal that weak export cartons are a primary cause of box collapse. The remediation strictly specifies double-wall (5-ply) “K=K” (Kraft-to-Kraft) master cartons. Furthermore, the oceanic transit environment introduces high humidity, which can swell paperboard dimensions by up to 5%, ruining the friction fit of telescope lids. The inclusion of desiccant packets within a sealed polybag is a mandatory chemical defence against this moisture incursion.

Perhaps the most sophisticated design challenge in jewelry packaging is the chemical interaction between the container and the contents. Tarnish is not merely an aesthetic nuisance; it is a chemical degradation of the metal surface, primarily silver sulfide ($Ag_2S$), resulting from reaction with atmospheric sulfur. A significant percentage of “tarnish” events are actually caused by the packaging materials themselves—a phenomenon known as “off-gassing.” Addressing these chemical interactions is paramount when responding to Richpack’s jewelry packaging customization inquiries regarding high-end silver storage.

All wood species contain organic acids, but the concentration varies dramatically. A major design flaw in luxury packaging is the use of high-tannin woods in direct proximity to silver without adequate barrier layers.

Dendrological Risk Assessment:

Adhesive Chemistry:

The glue used to assemble the box is another vector for sulfur. Solvent-based contact cements and rubber-based adhesives often continue to off-gassing sulfur compounds long after curing. For jewelry applications, water-based Polyvinyl Acetate (PVA) or aliphatic resin glues (yellow wood glue) are the only chemically safe options. They cure by evaporation, leaving an inert bond line that does not contribute to the sulfide load in the box.

Standard velvet linings are passive; they provide physical protection against scratching but do nothing to stop chemical corrosion. In fact, some synthetic velvets and felts are dyed with sulfur-based compounds that actively tarnish silver.

Active Scavenging Technology:

The remediation for tarnish-prone environments is the use of active scavenger cloths, such as Pacific Silvercloth®. This material is a cotton flannel embedded with thousands of microscopic silver particles. These particles act as “sacrificial anodes.” They react with and trap hydrogen sulfide gas in the air before it can reach the jewelry stored inside. The cloth literally “takes the bullet” for the jewelry, turning brown over decades as it becomes saturated with sulfur.

Comparison of Lining Technologies:

| Material | Mechanism of Action | Lifespan | Suitability |

| Standard Velvet | Physical cushion only. | Indefinite (Physical) | Low: No chemical protection; may off-gas dyes. |

| Pacific Silvercloth® | Active Scavenging: Silver particles trap sulfur gases. | 20–40 Years | High: The industry standard for silver preservation. |

| Anti-Tarnish Strips | Passive Absorption: Carbon/Copper matrix absorbs pollutants. | 6–12 Months | Moderate: Requires frequent replacement; good for sealed bags. |

| Treated Flannel (Zinc) | Active Scavenging: Zinc particles trap sulfur. | 5–10 Years | Good: Effective, though slightly less reactive than silvercloth. |

Restoring a vintage box often involves removing the original, deteriorated felt lining. This process can be treacherous if the adhesive is unknown. However, historical manufacturing practices provide a clue: most pre-1960s boxes used animal hide glue, which is water-soluble.

The Hydro-Saturation Technique:

To remove old felt without damaging the wood:

For modern boxes using synthetic adhesives (which will not dissolve in water), solvents like isopropyl alcohol or naphtha (lighter fluid) are required. These must be tested on the box’s finish first, as they can dissolve lacquer and shellac.

The functional lifespan of a jewelry box is frequently determined by its hardware. Hinges, locks, and catches are the moving parts of the system, subjecting the static wood chassis to dynamic stress. A common pathology in this domain is the “stripped screw syndrome,” where the repeated torque of opening the lid tears the wood fibers holding the hinge screws, leading to a loose or detached lid.

Simply tightening a screw in a stripped hole is a futile exercise; the wood fibers are compressed and sheared, offering no mechanical grip. The only permanent engineering solution is to replace the substrate material.

Step-by-Step Reconstruction:

The geometry of the hinge dictates the box’s opening mechanics. A common design flaw is the use of hinges that allow the lid to flop back 180 degrees, putting immense strain on the rear of the box.

Locks on jewelry boxes are often simple “warded” locks or “pressed-in” catches. A frequent failure mode is the misalignment of the catch (the hook on the lid) with the lock body. If a lock turns but fails to secure the lid, the catch is usually bent out of engagement range.

Diagnostic and Repair:

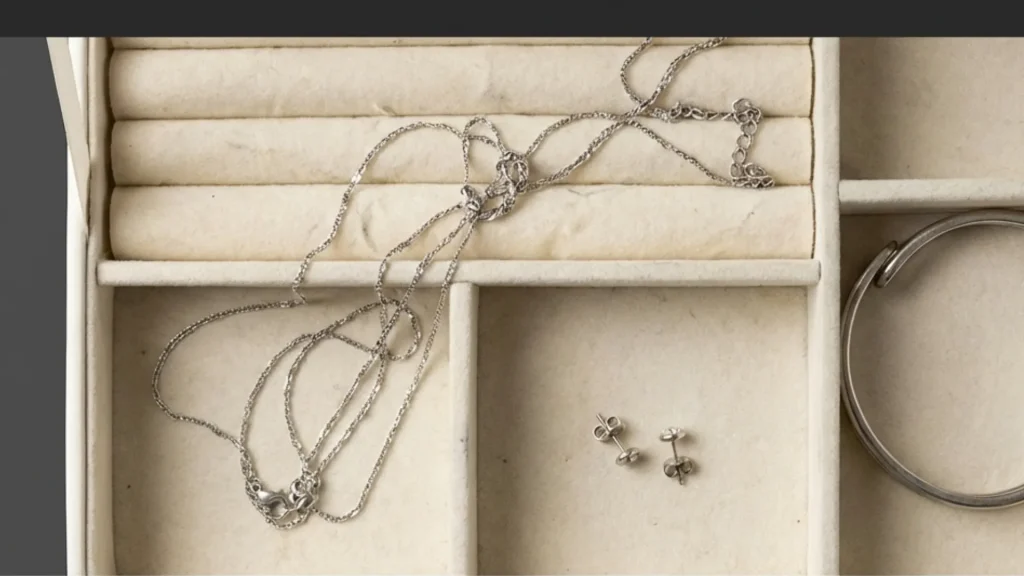

A jewelry box may be structurally sound and chemically inert, yet fail functionally if the interior architecture does not match the user’s collection. The “one-size-fits-all” approach of historical manufacturing has been rendered obsolete by the diversity of modern jewelry, from chunky statement rings to delicate layered necklaces. Analyzing Requests for Richpack’s personalized jewelry packaging customization shows a strong trend towards modular and adaptable interior designs. Knowing how to choose the right jewelry box for different types of jewelry helps in defining these interior specifications accurately.

The ring roll is the defining feature of a jewelry box. It must hold rings upright for display while exerting enough friction to prevent them from dislodging during transport.

Method A: The High-Density Foam Matrix (DIY/Retrofit)

For retrofitting existing boxes, high-density foam (such as closed-cell polyethylene or yoga mat material) is superior to open-cell sponge, which lacks the compressive resistance to hold heavy rings.

Method B: Solid Wood Routing (Heirloom/Custom)

For a more permanent and luxurious solution, solid wood ring rolls can be machined.

Fixed dividers restrict utility. The hallmark of a well-engineered custom box is modularity. The “half-lap” (or egg-crate) joint allows for the creation of rigid yet removable divider grids.

Fabrication Protocol:

Standardizing compartment sizes based on anthropometric data and jewelry dimensions prevents the “jumble” effect.

Optimal Grid Dimensions:

| Compartment Use | Dimensions (Inches) | Depth Requirement | Notes |

| Stud Earrings | 1.5″ x 1.5″ | 1.0″ | Shallow depth is critical for retrieving small backs. |

| Rings | 2.0″ x 2.0″ | 1.75″–2.5″ | Deeper clearance needed for high-setting engagement rings. |

| Bracelets | 3.5″ x 3.5″ | 2.0″ | Width must exceed bracelet diameter to prevent curling. |

| Necklace Channels | 2.0″ x 8.0″ | 1.0″ | Long, narrow channels prevent chain entanglement. |

Even the most structurally sound box will suffer cosmetic damage over decades of use. Restoring the finish on a high-gloss lacquer or polyurethane box requires specific techniques that differ from general furniture repair.

For deep scratches, dents, or gouges in a finished surface, “burn-in” sticks (lacquer or shellac resin sticks) offer a repair that integrates chemically with the finish, unlike soft wax fillers which merely sit on top.

The Burn-In Procedure:

If a repair crosses a prominent grain line, the burn-in will look like a solid patch. To fix this, use a fine-point graining pen or artist’s brush with pigment to draw the missing grain lines across the leveled fill before the final sealer coat is applied. This “trompe l’oeil” technique tricks the eye into seeing continuous wood figure.

For brands commissioning jewelry boxes, avoiding these flaws requires rigorous upstream quality control. The defects discussed—thin board, acidic wood, weak hinges—are often engineered into the product to save cost. Insights from Richpack’s custom jewelry packaging consultation requests suggest that proactive specification is the only defence against these quality fades.

Procurement managers must establish a “specification firewall” that explicitly prohibits common cost-cutting measures.

Critical Manufacturing Specs:

A strategic shift is required in how brands allocate budget. Currently, significant cost is sunk into disposable outer layers—ribbons, tissue, and textured papers—that are discarded within seconds. A more sustainable and brand-building approach—often recommended in response to Richpack’s inquiries about jewelry packaging customization—is to invest that capital in the permanent architecture of the box.

Recommendation:

Shift budget from disposable exterior embellishments to reusable interior modularity. A box with a magnetic closure and a high-quality, removable velvet insert (featuring the half-lap divider system) transforms the packaging from trash into a permanent storage solution. This ensures that the brand’s logo remains on the customer’s dresser for years, rather than in the recycling bin.

The remediation of design flaws in custom jewelry boxes is a discipline that merges the precision of engineering with the sensitivity of conservation. By understanding the structural physics of rigid board, the chemical interactions of tarnish, and the ergonomics of user interaction, manufacturers and restorers can elevate the jewelry box from a mere container to a guardian of value.

The solutions detailed herein—from the dowel-plug repair of stripped screws to the use of Pacific Silvercloth active scavengers—are not theoretical. They are practical, proven methodologies for correcting the systemic errors that plague the industry. Whether one is specifying a production run of 10,000 units based on Questions about bespoke jewelry packaging solutions by Richpack or restoring a single Victorian heirloom, the principles remain the same: stability, neutrality, and functionality. Adherence to these standards ensures that the box endures as long as the treasures it holds.

Lithography can help design and print unique jewelry boxes. This adds a personal touch to your jewelry. Choosing the right materials and preparing them well is key to making eco-friendly and attractive jewelry boxes.

These boxes enhance the unboxing experience, boost customer loyalty, and are eco-friendly. With precision laser engraving and bulk order discounts, they're a great packaging solution.

Today’s customers don’t just look at the product itself; they seek a memorable buying experience. How can an e-commerce jewelry brand stand out? The answer is making a lasting impression starts with custom packaging. For e-commerce, the product packaging is not merely for protecting a product but also a tool to advertise the brand and… Continue reading Fixing Design Flaws in Custom Jewelry Boxes: Practical Solutions

Charming Jewelry Boxes Inspired by Disney Characters | Cute Hello Kitty Gift Box Perfect for Princess Collections and Themed Gifting

Classy Jewelry Box Mirror Style for Elegant Storage – Customizable Mirrored Jewelry Boxes and Vanity with Jewelry Storage in Mirror Solutions

Creative Brown Paper Bag Puppets for Fun Crafting Activities – Learn How to Make a Paper Bag Puppet with Richpack’s Customizable Easter Paper Bags for Kids

Affordable Sustainable Packaging for High-Volume Jewelry Orders | Perfect for Wholesalers Seeking Scalable, Green Solutions at Competitive Prices

View More

Biodegradable Cookie Packaging for Small Bakeries | Eco-Friendly and Sustainable Solutions | Custom Designs Available

View More

Blue Leather Engagement Ring Boxes | Jewelry Packaging Wholesale – Richpack

View MoreJust submit your email to get exclusive offers (reply within 12 hours)